2.5 Dutch and Flemish Paintings in Polish Collections

Gerson offered only in passing a few observations concerning Danzig collections which included Dutch paintings. Relying on an article of 1934 by the then-still-young Niels von Holst (1907-1993),1 Gerson mentioned only the most important of the collections of rulers and princes. The information that he had at his disposal came from the then recent Polish-language publications by Tadeusz Mańkowski (1878-1956) [1] and Aleksander Czołowski (1865-1944) [2].2

1

Anonymous Poland

Portrait of Tadeusz Mańkowski (1878-1956)

Whereabouts unknown

2

Anonymous

Portrait of Aleksander Czołowski (1865-1944)

Lviv, University Library (Lvov)

3

Rembrandt

The Polish rider, c. 1655

New York City, The Frick Collection, inv./cat.nr. 1910.1.98

4

Juliusz Kossak after Rembrandt

The Polish rider, c. 1860-1865

Warsaw, Muzeum Narodowe w Warszawie, inv./cat.nr. MP 3991

With the collection of Stanislaus II August Poniatowski (1732-1798) Gerson named the same Dutch paintings to be found in a French summary of Mańkowski’s standard work.3 It is therefore puzzling that Rembrandt’s Polish Rider [3], which is included in this publication, is missing from Gerson’s overview, even though that work speaks so greatly to the imagination. Research into the dress and arms of the horseman establishes that they are authentically Polish, proving that the creator(s) of this famous work had a detailed understanding of Polish dress.4 The painting was in any case in Polish hands from 1791 to 1910. Around 1860 to 1865 Juliusz Kossak (1824-1899) made a smaller copy that is now in the National Museum in Warsaw [4]. The museum identifies the dress of the rider as that of a Lisowczyk or a Lisowski Kozak, named after the Polish-Lithuanian commander Aleksander Józef Lisowski (c. 1580-1616).5 At the time that the copy was made, the original was in the collection of the aristocratic politician Jan Dzierżysław Tarnowski (1835-1894) [5].

Even before 1942, the year in which Gerson’s Ausbreitung came out, the history of Dutch and Flemish art in Polish collections was already thoroughly complicated, as may be deduced from the historical introduction by Jan Kosten, found above. Gerson took historical knowledge more or less for granted around 1940. However, such knowledge is relatively slight with the generation that grew up in the West during the Cold War. The many raids by the Russians and Swedes and the three partitions of Poland did great damage to the art holdings. The national museums of countries such as Spain, England, France and Austria are filled with collections that were built up over the centuries by ruling dynasties. No such continuity in collecting occurred in Poland because, from 1572 on, the Polish kings were elected and therefore did not pass their collections on to their successors.6 Gerson limited himself in the Ausbreitung to the history of collecting up to the early 19th century, which he treated in connection with indigenous artists who were inspired by Dutch (and Flemish) art to be found in their country.

Countless art treasures were lost, went missing or were moved because of World War II. Especially after the upheaval of 1989 ever more information became accessible and great effort has been devoted to have works repatriated, often with success. In 1992 Lucia Thijssen published an important survey work entitled 1000 jaar Polen en Nederland (1000 Years Poland and The Netherlands), which includes a chapter on the history of Polish collecting of Dutch and Flemish paintings.7 In 2004 CODART8 organized a conference on Dutch and Flemish art in Poland and organized an excursion to Danzig, Warsaw and Cracow which provided participants with much new information. The Codart Courant reported in detail on these developments, and the lectures appeared in the form of valuable survey articles, including one by Hanna Benesz concerning Early Netherlandish, Dutch and Flemish paintings in Polish collections.9 The paper she presented for this publication ( § 6) is based on this lecture.

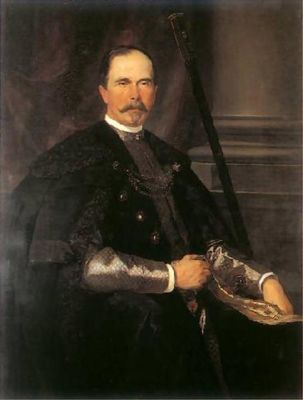

5

Henryk Hipolit Rodakowski

Portrait of Jan Dzierżysław Tarnowski (1835-1894), dated 1889

Łańcut, Muzeum Zamek (Łańcut)

Notes

1 One of these collectors is more closely examined in an article by Sander Erkens which follows below.

2 Mańkowski 1932 en Czołowski 1937.

3 Unfortunately the copy of this rare book in the RKD lacks illustrations, which in a remote past were subdivided over the RKD’s visual documentation.

4 Mańkowski 1932 p. 56, 389, cat. no. 1734, fig. 50. In 1984 Bruyn suggested in passing that the Polish Rider might not be by Rembrandt, but possibly by Willem Drost (Bruyn 1984). Since Bruyn made his remarks there has been an ongoing controversy about the attribution of the painting (Bailey 1994 and Bikker 2005, pp. 147-149). In 2011 Van de Wetering concluded that the painting was laid out by Rembrandt and painted substantially by him, with another artist possibly from his studio completing the work in order to make it more presentable for sale (Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings 1982-, vol. 5 [2011], no. V 20).

5 See Żygulski 1965 and Żygulski 2000.

6 Seipel et al. 2002, p. 10.

7 Thijssen 1992, pp. 184-203. The book came out in Polish in 2003.

9 Benesz 2004; http://www.codart.nl/downloads/Courants/courant8new.pdf.