7.2 Gdańsk: The ‘Golden Age’

Hans Vredeman de Vries is a good example of better-known masters, Netherlandish by birth, or at least obviously schooled in the Netherlands, who began to appear on the local ground starting with c. 1590. They commence a period of great growth in artistic influences imported from United Provinces and Flanders, which lasts for more than a generation, until mid-1620’s, or c. 1630, i.e. until the catastrophe of the first Swedish-Polish war. This time has been often called ‘the golden age’ of Danzig culture, and indeed, high quality artistic production is then paired with an unprecedented economic prosperity of the city. Vredeman, who was originally called to Danzig in the capacity of fortificator, left behind very numerous pictures here, of which the ones still surviving in the Main Town City Hall [1] provide the most extensive ensemble existing today of works by the artist in their original setting. They repeat more or less the master’s usual painterly pattern of fantastic architectural studies, populated with small figures.1 Vredeman was helped in the city by his son Paul, and by Hendrick Aerts (b. 1565/75), a local descendant of Netherlandish immigrants, who continued Vredeman’s ideas in painting after the latter left Danzig for Rudolfine Prague. Works by Aerts are rare, as he died already in 1603, but a Palace interior in the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam [2], executed a year earlier shows in its figures unmistakable details of Danzig costumes of the period.2 As already stated, Vredeman’s influence in Prussia was broader: his concepts were used, among others, by Isaac van den Blocke and Anton Möller the Elder, whose oeuvre will be discussed later on.

Isaac van den Blocke (c.1574-c. 1627), active in the first quarter of the 17th century, was son of the renowned stonemason Willem, and member of a family from Mechelen in Brabant that began to settle in Danzig in the 1560’s. Research on his oeuvre is still underway, but it can already be said that he was a prolific artist, painting both for numerous local churches, civic buildings and burgher houses. By far his most famous work – and the only one documented – is the allegorical and emblematic ensemble of paintings for the carved ceiling of the Red Chamber in the Main Town City Hall (1608-1609), of which the grandiose Allegory of Danzig [3] constitutes the centerpiece. In this prestigious picture, commissioned by the City Council and proclaiming its political program, Van den Blocke presents himself as heir of Netherlandish masters of c. 1580, with forms defined by fairly hard contour and – to a large extent – local colour. In paintings from later years, which can be securely attributed to the artist [4], he softens a bit his forms and palette, undoubtedly under influence of contemporary evolution of art in the Low Countries. One name of a Low Countries painter relevant both to the shape of van den Block’s figures and to his extensive landscape backgrounds, is Lucas van Valckenborch, though he also could have been inspired by a local celebrity - Anton Möller the Elder. In his later use of chiaroscuro in landscapes, van den Block also reaches to the experiences of the Frankenthal school.3 This versatile artist became one of the founders of the Danzig guild of painters in 1612, a belated organization that however displays in its regulations and activities some traits of art academies of the modern era.4

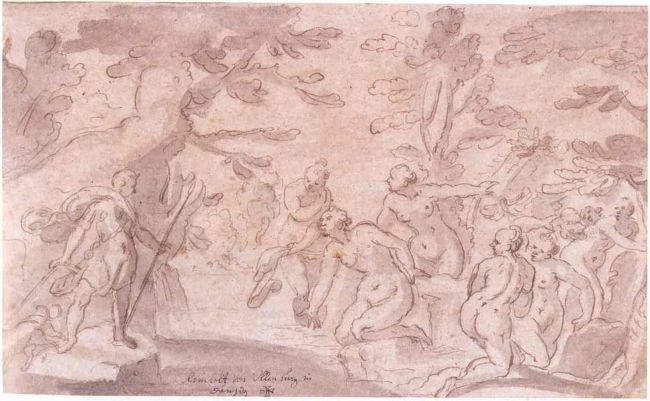

Two other names of Netherlanders that can be connected with the art of painting in Danzig at the turn of the 16th century, are the still enigmatic master Geert Janssen in den Enge (mentioned 1576-1628),5 and Rombout Uylenburgh (1580/85-before 1628). The latter, active in Danzig from around 1612, is especially interesting as cousin of Rembrandt’s wife, Saskia. He was the son of an ebenist to the King of Poland and lived at first in Cracow in the south of the country. After moving north, he became another co-founder of the Danzig painters’ guild, before allegedly returning to Amsterdam c. 1625. No existing works by this master were known until recently, when a signed pen sheet depicting Diana and Actaeon [5] from about 1620 surfaced, comparable with similar drawings by Abraham Bloemaert from Utrecht. Many more works are being attributed to him now, which in fact has been prompted by research linked to the Gerson Project.6

1

Hans Vredeman de Vries

The civil virtues, 1594-1595

Gdańsk, Muzeum Historycznege Miasta Gdańska (Ratusz)

2

Hendrick Aerts

David observes the toilet of Bathsheba; a servant leads her to his palace abode (2 Samuel 11:2-4), dated 1602

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. A 2528

3

Isaak van den Blocke

Allegory of Gdańsk trade, dated 1608

Gdańsk, Muzeum Historycznege Miasta Gdańska (Ratusz)

4

Isaak van den Blocke

The building of the tower of Babel (Genesis 11:3-5), probably 1611-1614

Gdańsk, Muzeum Historycznege Miasta Gdańska (Ratusz)

5

attributed to Rombout Uylenburgh

Diana and her nymphs surprised by Actaeon

Wolfegg, private collection Fürstlich von Waldburg-Wolfegg'sche Kunstsammlungen, inv./cat.nr. Kasten 67

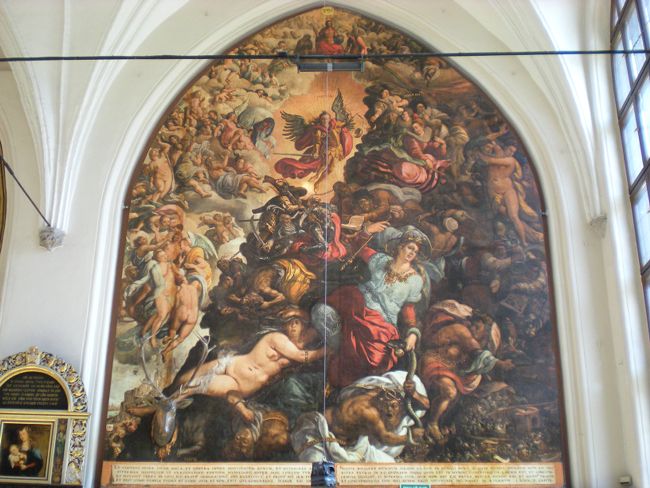

Among the artists of the city’s ‘golden age’, who were not Netherlandish by birth stands out the personality of Anton Möller from Königsberg in Ducal Prussia (c. 1563/1565–1611), perhaps the best northern German painter and draughtsman of around 1600. This excellent master, who joined in his work German and Netherlandish elements, appeared in Danzig around 1587 and died in 1611. The quarter of a century of his activity here, which produced over a hundred surviving drawings and around twenty paintings, must have been preceded by a very thorough schooling. Part of it was surely due to the conservative Königsberg milieu, which looked to Dürer and German masters of the earlier 16th century for artistic ideas; on the other hand, Möller displays in his painting very distinct affinities with Netherlandish artists of around 1570-1580, much like in the case of Isaac van den Blocke. His monumental and well-built figures with clearly defined contour disclose knowledge of works of such painters, who absorbed the lesson of Florentine-Roman Renaissance, as Pieter Aertsen, Maerten de Vos, or Anthonie Blocklandt, and lack the Venetian-inspired softness of forms of the 1590’s. This may be well seen in the huge Last Judgement (1602/3) [6] from the Danzig Artus Court, lost during the last war, or, for instance, in The Reconstruction of the Temple by King Joash [7] in the city’s National Museum from the same time. The main motif of this painting is clearly influenced by Vredeman de Vries, while linear vedutes in the backgrounds of other pictures by Möller reach to similar Netherlandish depictions from around 1580, like those executed by Hans Bol.

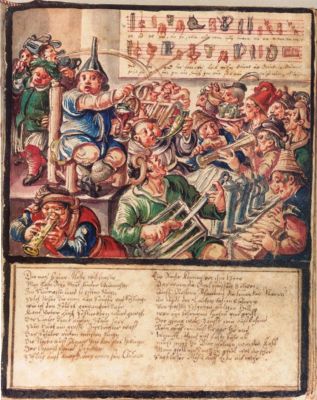

Synthesis of older German influences and newer ones, coming from the Low Countries, into a new, individual quality, achieved by the master’s outstanding individuality and inventiveness, is also characteristic of his drawings, predominantly executed in pen [8]. The precision and acute observation of the Dürer circle is linked here to technique and iconography borrowed from Hendrick Goltzius or Jacques de Gheyn. Along with the latter, and Roelandt Savery in Prague, Möller became one of Europe’s first artists to depict folk types from real life. He also excelled in producing gouache miniatures [9], outlined in few expertly brush strokes, and modelled to some extent on similar works by Pieter Aertsen, or Dirck Barendszoon.7

6

Anton Möller

The last judgment, c. 1601-1602

Gdańsk, Muzeum Historycznege Miasta Gdańska (Dwór Artusa)

7

Anton Möller

Reconstruction of the temple by King Joash: collecting gifts for the construction (2 Chronicles 24), c. 1602

Gdańsk, Muzeum Narodowe w Gdańsku, inv./cat.nr. MNG/SD/494/M

8

Anton Möller

Study of a standing peasant, dated 1599

Bautzen, Museum Bautzen, inv./cat.nr. L 653c

9

Anton Möller

Satirical representation of a drunken orchestre, after 1610

Kórnik, Biblioteka Kórnicka PAN (Polska Akademia Nauk), inv./cat.nr. BK 1436

Somewhat younger than Möller was Hermann Han (1580-1627/1628), another founding father of the painter’s guild, working in the city from around 1600 until his death, and born to a Dutch family living close to Danzig. His biography falls apart into two distinct periods: namely, around 1615 he converted from Lutheranism to Catholicism and was forced to move with his workshop to a small town. There he nevertheless continued to receive very lucrative commissions for large counter-reformation altar pictures (e.g. Coronation of Our Lady, Pelplin cathedral, 1623) [10], which brought him much fame and strongly influenced painterly production in northwestern Poland at least until mid-century. In such paintings, Han obviously looked for inspiration towards religious compositions from the Catholic art centre in Southern Netherlands (for instance, the ones produced by Otto van Veen), but he also magnified the schemes of small, popular devotional prints produced by Flemish workshops like the ones of Wierix or Collaert families. Dominating Flemish influences are also visible in earlier, pre-Catholic part of the artist’s oeuvre – in small, allegorical cabinet pictures of considerably high quality, rich in intellectual and emblematic contents. Probably the most interesting is a painted cembalo cover, depicting an Allegory of marital virtue [11], executed in 1600 for the daughter of burgomaster Johann von der Linde (in 1995 Galerie Lingenauber, Düsseldorf). Such works by Han, showing small human figures set against an extensive land- or cityscape, recall the oeuvre of Louis de Caullery, or David Vinckboons, in which deep, vibrant colour hues are joined to soft, painterly forms of Venetian origin. These latter traits are characteristic of the Danzig artist also in the later phase of his activity.8

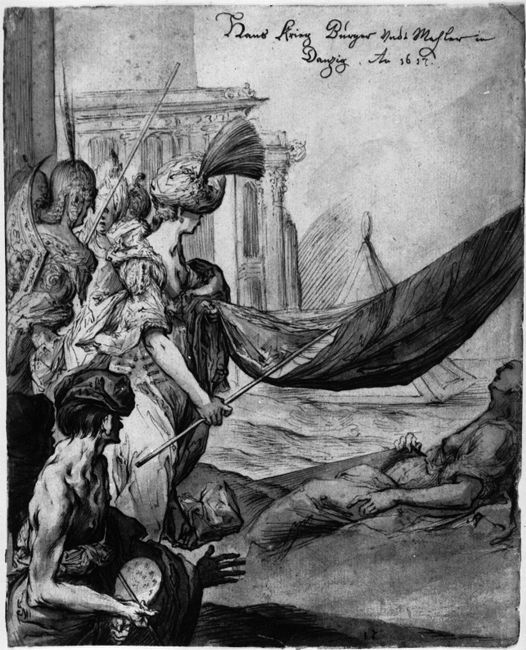

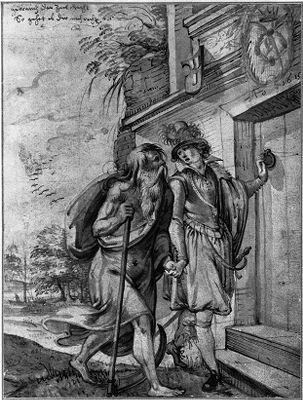

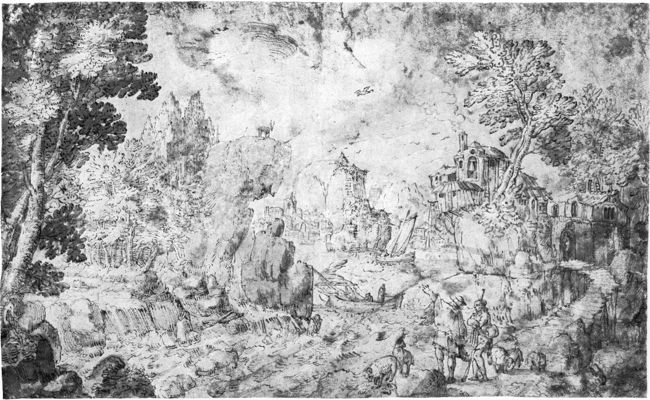

The first master promoted in the city’s newly founded painter’s guild – in 1616 - was Johann Krieg (c. 1590-1643/47). This somewhat younger artist is today unknown by painterly work, but a considerable number of his pen drawings has survived, all of which testify to his inventive force and formal abilities. Krieg’s surviving oeuvre can be divided into two distinct channels. On one hand, he produced a number of highly mannered, even grotesque or bizarre allegories [12], pointing to the artist’s obsession with then much exploited subject of war and art, which peculiarly fits with his surname. This series, developed in the years 1617-1622, around the beginning of the Thirty Years’ War, is dependent in its forms on decorative drawings by Hans von Aachen from Prague and on prints made after them by the Fleming Aegidius Sadeler. Parallel to such works, Krieg drew compositions much more delicate and classical in appearance [13], in which he shows influence by such Dutch masters as Willem Buytewech, or David Vinckboons. These inspirations lingered on in the master’s work after – another such case in the milieu – he converted to Catholicism in 1632 and became a lay brother in the Cistercian convent of Pelplin. Krieg also executed a few independent landscape drawings [14], rare in Danzig, modelled especially after another Netherlandish artist from Rudolfine Prague, Peter Stevens.9

10

Herman Han

Coronation of the Virgin Mary, 1623-1624

Pelplin, Bazylika katedralna Wniebowzięcia Najświętszej Maryi Panny w Pelplinie

11

Herman Han

Allegory of marital happiness and virtue: elegant company with a vie of the city of Danzig, 1600

Paris, Düsseldorf, art dealer Galerie Lingenauber

12

Johann Krieg

A group of female figures: Allegories of Art, War and Eternity, dated 1617

Poznań, Muzeum Narodowe w Poznaniu, inv./cat.nr. TPN 1413

13

Johann Krieg

Young man and Father Time: Allegory of Time, dated 1615

Berlin (city, Germany), Kunstbibliothek (Staatliche Museen zu Berlin), inv./cat.nr. HdZ 34 (Lipp 8645 - Hzl 3.12)

14

Johann Krieg

Mountainous landscape with shepherds, c. 1620-1630

Amsterdam, private collection Bernard Houthakker

Notes

1 By far the most complete publication on Vredeman to date is Borggrefe/Fusenig/Uppenkamp 2002.

2 The most extensive publications on this short-lived and little known painter are Vermet 1995 and Vermet 1996.

3 Surprisingly little has been written on this considerably high quality painter and a monograph in any form is badly lacking; for now see, however, Tylicki 2005B, pp. 138-141 and passim, and Tylicki 2012, p. 314. 56-62. Archival data is provided in print by Pałubicki 2009, pp. 589-590. The latter publication is often helpful, but especially in the case of little-known painters, as – even if not devoid of errors, notably in commentaries - it is the first attempt to collect in a systematic way written sources which were never analyzed in print before. It may be consulted for most Gdańsk painters, also when it is not cited in footnotes of the present text.

4 For instance, the candidates for masters were expected to submit two works in oil and water techniques; the subject was a secondary question, which is unusual for guild rules. There is only one very rare publication that discusses the history of the organization and some aspects of its activity: Cuny 1912; see also Tylicki 2005A, pp. 15-16.

5 For this artist, whose works are not ascertained, and his two sons, supposedly also painters, see now Pałubicki 2009, pp. 202-204. Although the name sounds Netherlandish, which seems plausible to Pałubicki, he supposes the man was from Danish Schleswig. The sources themselves note Königsberg origin, if they pertain to the same person. The issue requires further clarification.

6 Information on this artist is dispersed; apart from the essay by Erik Löffler above in this publication, see Tylicki 2006 and Lammertse/Van der Veen 2006, passim, and Van der Veen 2013.

7 Most information on Möller is provided by Gyssling 1917, Ehrenberg 1918 and Tylicki 2005A, pp. 177-212 and passim. A new monograph on the artist is in the course of preparation by the author of this paper.

8 Not typically for Gdańsk, this master has been the subject of three monographs, the most recent of which is Pasierb 1974. There have been important new discoveries concerning his person and work, however, which are summed up in Tylicki 2008Aand Tylicki 2009.

9 The only monograph on Krieg is an old essay (Secker 1924), but see also Tylicki 2005A, pp. 162-176 and passim, and Tylicki 2012, pp. 316-317, with additions and corrections.